|

| Three kinds of Spanish empanadillas, clockwise from the top: Catalan panadons with spinach filling; fried tuna empanadillas, and meat-filled Sephardic burekas. |

Are they turnovers? Hand pies? Pasties? Let’s just call them empanadillas, Spanish for little pastry packages filled with meat, fish, vegetable or cheese. (Large, pie-size ones are called empanadas.)

Empanadillas have been popular in Spain since, maybe, the 7th or 8th century, when Arabs introduced them during the Moorish caliphate. (Known as

sambousek, they are still popular in the Arab countries of the Middle East.)

In medieval times, Spain’s Sephardic Jews lived alongside the Moors in Córdoba, Sevilla, Toledo and many other towns. From their neighbors, they learned the art of making little savory pastries, which became part of cherished foods for special occasions.

After 1492 (the year Queen Isabel and King Ferdinand conquered the last Moorish kingdom of Granada; funded Christopher Columbus’s first voyage to the unknown, and issued the expulsion order against Spain’s Jews), many of Spain’s Sephardim, forced to flee, were welcomed by the Ottoman Empire (present-day Turkey). There Moorish empanadillas met Turkish

börek, also a filled pastry. The Spanish-speaking Jews (their lingo is Ladino) took on the Turkish name, but added the Spanish diminutive ending, calling their turnovers

borekas or

burekas.

|

| Two kinds of burekas made by the Sisterhood at Congregation Or VeShalom in Atlanta. They are a little larger and much prettier than the ones I made. |

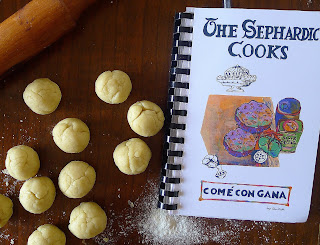

I sampled modern-day burekas made by the Sisterhood of the Sephardic Congregation Or VeShalom in Atlanta, Ga. The women of the Sisterhood gather every week to prepare quantities of burekas, with fillings of spinach, eggplant and meat. (See a video of bureka making

here.) I also purchased their cookbook,

The Sephardic Cooks, (published by Congregation Or VeShalom Sisterhood; Atlanta, GA.; revised edition 2008), which includes recipes for burekas (and dozens of other recipes with Spanish-sounding names such as

boyos,

huevos con tomate,

apio con avas,

pescado al orno,

pastelles, and

arroz con garbanzos).

Back in the 15th century, as the Sephardim were dispersing east, Spanish conquistadores took the empanadilla west to the New World, where it became the beloved empanada of Argentina and of Venezuela, where the meat or cheese filling is enclosed in a maize-flour dough.

Here are three sizes of empanadillas, three different types of pastry dough, three fillings and two cooking methods (two are baked; one fried). You can mix and match them to suit yourself. The yields are given for the sizes used in each recipe. If you make them larger, you’ll have fewer; smaller and you’ll make more. I think I would prefer the burekas larger (6 inches instead of 4) and the spinach panadons smaller ((8-inch ones were kind of floppy).

|

| The most typical Spanish empanadillas--filled with tuna and olives and fried. |

|

| Catalan panadons are filled with spinach, pine nuts and raisins. |

|

| My rendition of meat-filled Sephardic burekas. |

Tuna-Olive Turnovers

Empanadillas de Atún

|

| Black or green olives give the tuna filling zest. |

These are the most typical empanadillas in Spain, a part of home cooking. They can be put together with ingredients in the pantry. Even the pastry rounds can be bought packaged for quick preparation. These empanadillas are perfect for anything from a picnic to school lunches to a cocktail party.

The empanadillas are usually fried, but they can be baked instead. They can be served room temperature.

I used 2 (110-gram) cans of bonito del norte (albacore tuna) for the filling. Either green or black olives work in the filling. If you use pimiento-stuffed green olives, use ¾ cup and skip the pimiento. The tomato sauce required here is canned tomate frito, a thick, smooth tomato sauce (not concentrate).

The filled turnovers can be frozen before they are fried. Place them on a baking sheet and place the sheet in the freezer. Once the turnovers are frozen, transfer them to a bag or container. When ready to serve, defrost the turnovers 2 hours before frying as directed.

Makes about 30 (3 ½ -inch) empanadillas.

|

| Mix tuna for the filling. |

1 cup drained canned tuna (7-ounce can)

½ cup pitted olives, chopped

¼ cup red pimiento, chopped

1 hard-cooked egg, chopped

¼ cup thick tomato sauce

2 tablespoons finely chopped onion

1 tablespoon chopped parsley

Pinch of fennel seeds

1 tablespoon brandy or Sherry

Pinch of cayenne

1 teaspoon vinegar

Salt, to taste

Dough for Empanadillas I (chilled)

Flour, as needed

Olive oil for frying

Place the tuna in a bowl and break up the chunks with a fork. Add olives, pimiento, egg, tomato sauce, onion, parsley, fennel, brandy, cayenne and vinegar. Mix well. Taste the mixture. It should be strongly seasoned. If necessary, add more salt, vinegar or cayenne. (Filling can be prepared a day in advance and refrigerated, covered, until ready to fry the empanadillas. Drain off any accumulated liquid before filling the empanadillas.)

|

| Divide dough before rolling and cutting. |

Divide the ball of dough into four pieces. Place one piece on work surface; keep remaining dough refrigerated. Dust rolling pin with flour and roll out dough as thinly as possible. Use a 3 ½ -inch cutter to cut 4 or 5 circles. Gather up scraps of trimmed dough and return them to the refrigerator.

|

| Fold dough over filling and crimp edges. |

Place a teaspoon of tuna filling on each of the circles. Fold over and press the edges together. Use a fork to crimp together the edges, sealing in the filling. Place the empanadillas on a baking sheet as they are formed. (If necessary, use a knife or offset spatula to lift them off the work surface.) Continue rolling and filling the empanadillas.

Place oil to a depth of ½ inch in a skillet. Heat until oil is shimmering, but not smoking. Fry empanadillas, 5 or 6 at a time, until browned on one side. Carefully turn them and brown reverse side. (If any of the empanadillas open while frying, skim them out immediately to prevent the oil from splattering.) Remove the empanadillas and drain on paper towels. Continue frying remaining empanadillas in small batches.

Dough for Empanadillas I

Masa para Empanadillas I

This is a shortcrust pastry made with olive oil instead of butter. Don’t knead it as for the other empanadilla doughs. Gather into a ball, pressing to combine the ingredients, and chill it well before rolling out.

Makes about 30 (3 ½-inch) empanadillas

2/3 cup olive oil

½ cup cold dry white wine

½ teaspoon salt

3 ¼ cup flour + additional for rolling out

Combine oil, wine and salt in a mixing bowl. Use a wooden spoon to stir in the flour. Gather the dough into a ball and squeeze it a few times to combine well. Chill the dough for at least 1 hour or overnight.

Divide the dough into 4 pieces. Roll out one piece at time, keeping the rest refrigerated. Refrigerate any scraps of dough before rolling and cutting them.

Empanadillas with Spinach

Panadons amb Espinacs

|

| Like a spinach sandwich--savory spinach with raisins and pine nuts wrapped in a yeast dough. |

This is a Catalan version of the Spanish turnover (panadons is just the Catalan word for empanadas). It’s not unlike the Sephardic bureka, but made with a yeast dough.

You will need a 14-ounce package of frozen spinach or 2 (10-ounce) bags of fresh spinach leaves to make the filling for these empanadillas. Drain the thawed or cooked spinach well.

Makes 6 (8-inch) empanadillas.

2 ¼ cups cooked, drained and chopped spinach

3 tablespoons olive oil

¼ cup pine nuts

2 cloves garlic, chopped

¼ cup seeded raisins

2 teaspoons fresh lemon juice

Salt

Freshly ground black pepper

Slices of soft goat cheese (optional)

Dough for Empanadillas II (yeast dough)

1 egg beaten with 1 teaspoon water

Heat the olive oil in a skillet and sauté the pine nuts until they are golden. Add the garlic, then raisins and chopped spinach. Season with lemon juice, salt and pepper. Cook until spinach is tender and all the liquid has cooked away.

Let the spinach cool completely before proceeding to prepare the empanadillas.

|

| Spoon filling on rounds of dough. |

Roll out the dough to make 6 (8-inch) circles. (Use a bowl as a guide and cut the dough with a knife.) Place 2 tablespoons of spinach filling on one half of each round. Push slices of cheese, if using, into the spinach. Fold one half of the dough over the filling. Roll the edges together, pinching them firmly to seal the packets of dough.

Preheat oven to 350ºF/ 180ºC. Line a baking sheet with baking parchment.

Place the empanadillas on the baking sheet and bake until they are golden and dough is completely baked, 35 minutes.

Dough for Empanadillas II.

Masa para Empanadillas II

This soft, stretchy yeast dough makes a bread-like casing for the filling. If you are expert at making pizza dough, you can probably stretch the balls of dough into rounds. Otherwise, roll them out and use a pan lid or bowl as a guide to cut the dough into circles.

Makes enough dough for 6 (8-inch) empanadillas.

½ teaspoon active dry yeast

¼ teaspoon sugar

2/3 cup very warm water

2 ¼ cups flour + more for rolling out

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon sesame seed (optional)

¼ cup olive oil

Place the yeast and sugar in a small bowl and add the warm water. Allow the yeast to stand until it is bubbly.

Place the flour in a mixing bowl. Add the salt and sesame seed, if using. Make a well in the center of the flour. Add the oil and yeast water. Use a wooden spoon to mix in the flour and liquids.

Turn the dough out on a lightly floured board and knead the dough until very smooth and elastic, adding the least amount of flour to the board to keep the dough from sticking.

Gather the dough into a ball and place it in a lightly oiled bowl. Cover with a damp cloth and place in a warm place to rise, about 90 minutes.

|

| After yeast dough rises, punch it down before rolling. |

Punch down the dough and knead it briefly. Divide it into six egg-sized pieces. Pat and roll the balls of dough into 8-inch circles.

Burekas (Sephardic Turnovers)

Empanadillas Sefardíes

This recipe for burekas comes from The Sephardic Cooks, published by the Sisterhood of Congregation Or VeShalom in Atlanta, GA. Besides the basic dough, the cookbook includes recipes for several different fillings. I’ve used the one for meat filling.

The recipe calls for “canned tomatoes, strained through colander with juice.” I used canned tomate triturado. Every cook adds a personal note—mine was to season with some allspice. Having tasted the meat burekas made by the congregation Sisterhood, I thought mine were not as juicy. I’m thinking that is because Spanish beef is dryer, not so fatty as American meat. Also, their burekas were larger than the 4-inch ones I made.

The baked burekas freeze well.. To serve, thaw them and reheat in a hot oven.

Makes enough filling for 36 (4-inch) burekas.

2 tablespoons olive oil

1 medium onion, chopped

1 pound ground beef

½ cup sieved canned tomatoes, with juice

2 tablespoons long-grain rice

½ teaspoon salt

Freshly ground black pepper

½ teaspoon allspice

¼ cup chopped parsley

1 hard-cooked egg, chopped

Dough for Empanadillas III (burekas)

1 egg, beaten

1 teaspoon sesame seed (optional)

Heat the oil in a skillet and sauté the onions until softened. Add the ground beef and fry it, breaking up the lumps with a fork, until it loses its red color. Add the tomatoes and juice, rice, salt, pepper and allspice. Cover and simmer until the rice is tender, about 20 minutes.

Remove from heat and add parsley and chopped egg. Allow to cool. (Filling can be prepared a day before rolling and filling the dough.)

|

| A spoonful of meat filling. |

Roll out and cut balls of empanadilla dough for burekas. Place a heaping teaspoon of filling mixture on one side of a circle of dough.

Fold over into half-moon shape. Press the edges together, then roll and pinch the edges to seal the dough. Place the filled burekas on a baking sheet that has been oiled or lined with baking parchment.

|

| Roll and pinch the edges together. |

Preheat oven to 400ºF.

Brush the burekas with egg. Sprinkle them with sesame seeds.

Bake the burekas until golden, about 30 minutes. Cool them on a rack.

|

| Burekas are brushed with beaten egg and sprinkled with sesame before baking. Cool them on a rack. |

Serve the burekas hot or room temperature.

Dough for Empanadillas III

Masa para Empanadillas III

This hot-water pastry dough is the one used for the bureka recipe. It’s super easy to work. Oil in the mix keeps the dough from sticking to the board, needing no additional flour.

I used a recipe from The Sephardic Cooks, Their recipe calls for “vegetable oil.” In my kitchen in Spain, I use olive oil exclusively. It also calls for White Lily flour. I used all-purpose flour. I made half the quantities given in the book.

½ cup olive oil

1 ¼ cups water

½ teaspoon salt

4 cups flour + additional if needed

Place the oil, water and salt in a large pan. Bring to a boil, remove from heat and immediately stir in the flour. Use a wooden spoon to mix the dough, then turn it out on a board and knead until smooth. Add additional flour only if dough seems sticky.

|

| Roll out the dough into walnut-sized balls. This recipe comes from The Sephardic Cooks. |

Roll the dough into 36 walnut-sized balls. (If preparing in advance, cover them with a cloth so they don’t dry out.)

Roll out each ball thinly. Use a 4-inch cutter to cut each into circles. Gather up the dough trimmings, form balls and roll and cut them in the same manner. The dough is now ready for filling.

|

| My consuegra, Juana, fries empanadas venezuelanas, made with corn meal and filled with meat or cheese. A New World version of Spanish empanadillas. |

Here are more types of dough for empanadas: